Tens of thousands of New Zealanders are thought to have myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), formerly known as ‘chronic fatigue syndrome’. Yet the disease remains largely neglected in medicine and politics alike.

The number of ME patients, those suffering from chronic fatigue and other symptoms, living in Aotearoa may have doubled in recent years, according to ME Society (ANZMES) estimates. The group has updated its earlier appraisal, drawing on an international prevalence rate based on pooled data. Applying this to our population and adding anticipated new cases triggered by Covid infection, the group’s estimate has risen from roughly 25,000 to 65,000.

If this estimate is correct, that would be more than the number of New Zealanders with rheumatoid arthritis, lupus and multiple sclerosis combined. Compared to most chronic illnesses, there’s only patchy medical and public awareness, little tailored health care, and very little research investment.

Aotearoa lacks an official, data-confirmed prevalence rate for ME, but the appraisal from ANZMES appears broadly consistent with estimates from other countries.

Emerging studies point to a trend where a large subset of people with persisting Long Covid may be developing ME. Overseas estimates suggest a sky-rocketing of new ME cases since the pandemic began, but the picture in Aotearoa is not yet clear and may differ in light of our initially low Covid spread. It’s crucial to remember that Covid hasn’t gone away. New Zealanders are still getting infected each week – wastewater testing last week showed the highest Covid levels all year – and every new infection carries a risk of Long Covid.

Viruses are a common cause of ME, alongside genetic and other factors, so it makes sense that the Covid virus may also initiate the illness in some people. The pandemic’s long tail is likely driving the suspected jump in numbers with ME here. Other contributors include an expected rise in number over time if many aren’t recovering, and the effect of a potential undercount in earlier years.

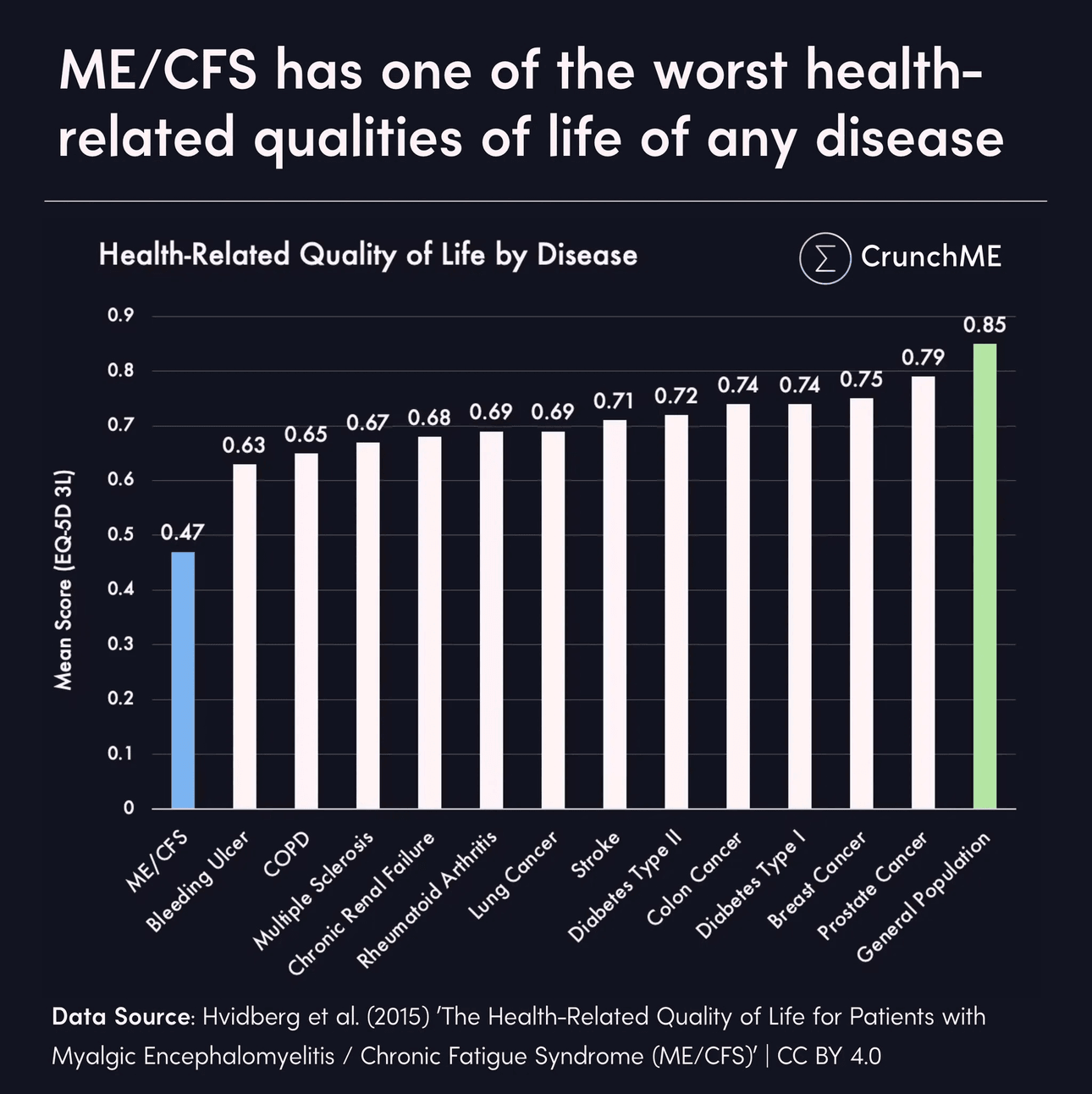

ME is a serious, long-lasting illness that stops people from being able to do their usual activities. The disease makes physical and mental exertion difficult, and can dramatically slash how much activity a person can handle.

It’s way more of a threat than “chronic fatigue syndrome” suggests. Most patients – up to 75% – need to stop or reduce their work. An estimated one in four are fully housebound or bedbound. With ME, your body’s energy battery recharges extremely slowly, and has a much smaller capacity overall. People severely affected may only get a total of 5% (or less) of the energy they had before getting ill, and it can take weeks, months or longer to recharge.

Far beyond tiredness, the hallmark feature of ME is “Post-Exertional Malaise” (PEM) – an extreme worsening of symptoms after even minor physical or mental exertion. This can trigger a “crash” lasting for days, weeks or longer.

Attempting to push through can greatly worsen symptoms and may lead to long-term deterioration. Those with severe ME become extremely disabled, needing fulltime care.

Many Long Covid patients have symptoms that match ME: are they the same thing? Not fully, but they seem closely related. Post-Covid ME is a subset of a bigger Long Covid umbrella, which covers various conditions including post-intensive care syndrome and autonomic disorders. Some people have both diagnoses; in future this may change as more is understood.

Affecting all ages including kids, ME disrupts the brain, immune system, and metabolism. It’s recognised as a physical disease by the World Health Organization (since 1969). Science supports this: multiple studies show many distinct biological abnormalities in people with ME.

But ANZMES President Fiona Charlton says she still hears of health professionals here claiming that ME is psychological in nature, based in the mind. In an interview for World ME Awareness, Charlton put the claim to Jaime Seltzer, US patient advocate, Stanford researcher and one of Time Magazine’s 100 most influential health leaders. Her response:

“This was never acceptable. But we know so much more than we did in the late 80s, early 90s when these diseases were first beginning to be known, that there’s genuinely no excuse for that anymore.”

Why is it vital for the public and doctors to understand these illnesses? If people truly realised the serious consequences when patients push too hard, forcing themselves back to work or exercise — they could be helped to avoid getting worse.

Bizarrely though, there’s been barely any political leadership on either illness in Aotearoa. There was one Health Select Committee inquiry into ME care back in 2012 (with no change or follow-up), little-to-no media advocacy from MPs, and no work programme or policy in the Health Ministry.

Our public health system has no dedicated services for ME patients, and no ME specialist doctor. There’s one clinic for Taranaki health staff with Long Covid, with no dedicated funding. Other Long Covid pilot clinics were discontinued.

Australia is funding biomedical research far more generously than us (though a lot more investment is still needed). Australia’s parliament has long completed an inquiry into Long Covid, including investigation of ME.

In contrast, the first report of New Zealand’s Royal Commission into the Covid response contains a fleeting mention of Long Covid, and made clear – after having sought input from affected (unwell) patients – that Long Covid was seen as outside the scope.

In many other countries (e.g. UK, US, Canada, Germany, Austria), at least some MPs or ministers are calling for change. Some sizeable investments in research are under way. And other nations have at least provided a number of specialist services for people with ME and Long Covid, for example the US and UK.

ANZMES has been urging political leaders to reclass ME as a disability for more than a decade, and has recently released an urgent call to action for MPs. The condition meets official disability definitions, for both New Zealand and the UN, yet ME patients can’t access sufficient disability support services. Some of the most severely sick patients in Aotearoa can only access three hours of caregiver support per day, when they require 24/7 care.

Immediate reform is required, the group says, to save the billions of dollars that ME costs the country. Australia’s price tag is cited – ME costs Australia’s economy about $14.5 billion AUD each year. This figure includes direct health care system costs, out-of-pocket expenses, the cost of accessing health care, and the indirect cost of lost income.

The pandemic could only compound the price tag. Researchers here think Long Covid might cost us about $2 billion annually – 0.5% of GDP – in lost productivity. Recent modelling from Germany put the combined cost, for both Long Covid and ME, at 1.5% of GDP in 2024.

The cost of doing nothing is high, for our people and our purse. The government must act to prevent further ballooning of these illnesses.

ANZMES says solutions are available that can help to improve individual outcomes and reduce healthcare strain. Among other policy actions, they suggest bringing in a new nationwide tracking system – to code, track and report on ME and Long Covid across health services – and to include both diseases in national health research with more sustained funding.

The ongoing toll of ME and Long Covid could be minimised by stronger measures to lower the spread of Covid and other infectious diseases, since it’s possible to lower or even prevent new cases of chronic illness triggered by pathogens including the Covid virus. This will require action, such as wider eligibility for vaccines and anti-viral treatments, masking measures, and cleaning the air in places like schools and childcare.

It’s time for our political and health leaders to stop the denial and act – a rising tide of affected New Zealanders can’t be ignored.

Information and support: ME Support, Long Covid Support Aotearoa, Complex Chronic Illness Support