In the 1980s and 90s one of the funnest places in Ōtautahi was an amusement park named after the reigning monarch. Danica Bryant revisits the home of Driveworld, Cloud 9, a big maze and other attractions.

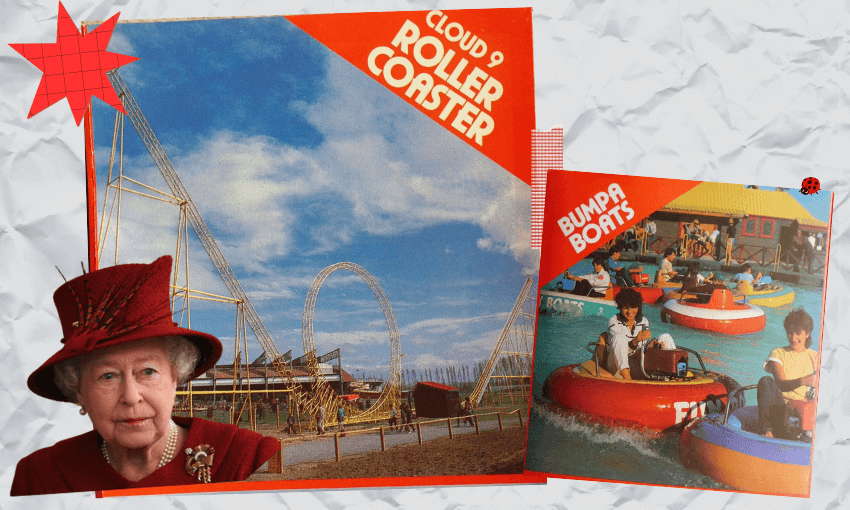

Queen Elizabeth II may not have loved rollercoasters, but in New Zealand, we built her one anyway. For Christchurch families, the name Queen Elizabeth II Fun Park – QEII for short – likely triggers vivid memories of dangerous mine trains, wild bumper cars and makeshift excavation sites. And although QEII Fun Park is long gone today, there’s still plenty of fun to have in remembering this iconic attraction.

QEII began not as a haven for thrillseekers, but for international athletes. In preparation to host the 1974 British Commonwealth Games, a brand new sports stadium was constructed in New Brighton, Christchurch. Named after the leader of the Commonwealth, who visited during its opening, QEII Stadium originally housed swimming and diving pools, a running track and a cricket ground.

After the Games, the stadium became a popular music venue, hosting legendary acts like David Bowie, AC/DC and The Beach Boys. As the QEII complex only became more popular, the Christchurch council brainstormed ways to expand.

By 1980, they’d struck up a lease with amusement enthusiast Colin Wood to operate a small attraction named Driveworld. At Driveworld, families could take model machines for a spin around a mock construction site, combining entertainment with earthmoving education.

Driveworld notably featured Wood’s unique original attraction, the Rollerballs. Rolling aluminium cages attached to three-wheeler motorbikes made for an uncomfortable but exhilarating ride experience. After guests tested the prototype at Driveworld, Wood sold the design to a Japanese company who purpose-built an arena for their own version.

Driveworld’s successful opening compelled the council to expand the stadium’s surrounding land into a fully fledged amusement park. Leasing out land to independent amusement operators, QEII Fun Park opened in 1983, right beside the existing pools.

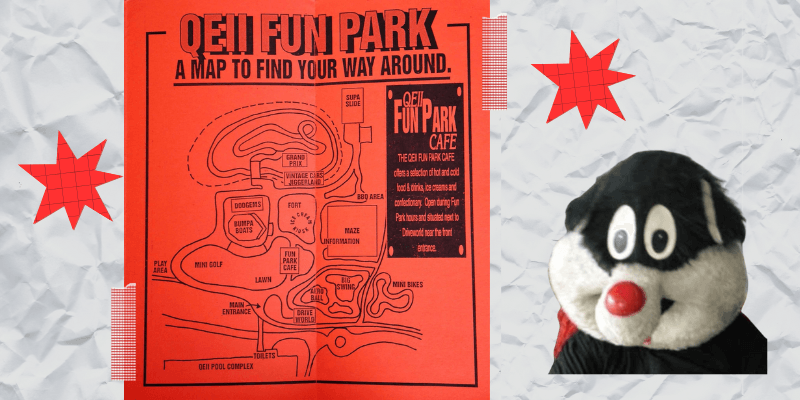

Unlike most of its competitors, the fun park operated more like a carnival than a permanent park. Patrons bought individual ride tickets rather than paying a singular entry fee. This meant they could freely explore the park without riding, or alternatively, take advantage of multi-ticket deals if they tackled every attraction.

Most of QEII Fun Park focused on appealing to families. Guests could take a swing at mini golf, battle on the dodgems and bumper boats, get lost in a two-storey maze, drive around race cars created at the nearby Paterson Brothers tyre shop, or explore the fort, giant slide and big swing.

The Supercat mascot also frequented the grounds as a walkabout character. Although the Supercat bore a striking resemblance to Looney Tunes’ Sylvester, with his big red nose and black and white fur, he looked just off-brand enough to uniquely represent QEII.

But the park’s most memorable attraction was undoubtedly Cloud 9, also known as the Runaway Minecoaster. Opening in 1985, this steel shuttle coaster was a simple but powerful beast. The chain lift hill dragged riders backwards before dropping them directly into a singular loop, then the cycle repeated in reverse. It may have been a gimmick, but what a gimmick it was in little old New Zealand. Not only was Cloud 9 the first and still only coaster to operate in the South Island, but it was also the country’s first inverting coaster, tipping riders upside down one year before Rainbow’s End opened their Corkscrew Coaster in 1986.

Cloud 9’s construction process is largely a mystery – there is no record of any established company building the behemoth, suggesting owner Bill Finnerty actually built it in-house. This type of private construction is incredibly rare in modern coasters, due to high costs and the extreme difficulty of inexperienced builders adhering to safety standards. Cloud 9’s only potential connection to any official coaster company is a Zamperla train left with North Island business Mahons Amusements, who theorise it may be the coaster’s abandoned vehicle.

Unfortunately, Cloud 9’s lifespan was brief and extremely troubled. Whilst most coasters last several decades with proper refurbishment, Cloud 9 barely reached four years standing. Rumour claims the coaster failed to meet safety regulations, with guests recounting the ride swaying side to side in the wind, but there isn’t any hard evidence of this. What’s certain is that the council suffered constant noise complaints from neighbours overwhelmed by the roar of the coaster as its screaming riders hurtled down the track.

To reduce the noise, Finnerty neutered Cloud 9’s thrills around 1988 by removing its loop. With almost no photographic evidence of this second layout, it’s unclear whether Finnerty transformed the coaster into a spike where riders valleyed in between two ramps, or merely one steep hill. Regardless, the coaster was decidedly less exciting without its central element. But even worse, it was just as loud as it had been before, leading to Cloud 9 closing in 1989.

Nevertheless, QEII Fun Park continued operating successfully throughout the 90s. Around this time, Richard Smit took ownership of the Driveworld section, working his way up from attendant to owner. But by the turn of the century, Driveworld and the fun park at large were up against the impossible challenge of the council redeveloping the neighbouring pool complex. They determined the fun park’s initial 25-year lease would not renew past its end in 2005, and quickly bought up remaining attractions to make space for the new pools.

Major players like the mini golf and bumper boats were the first to go. The playground structures and food kiosks soon followed suit. Driveworld outlasted most of the park, hoping to trade until the lease’s end, but revenues rapidly dried up due to the lack of attractions, causing total closure in July 2000. Themed to the lost city of Atlantis, the new pools opened in 2002, but they essentially replaced the fun park itself, leaving many rides in search of a new home.

Mahons Amusements purchased the dodgems, but they sat abandoned for many years before facing the scrap heap due to age. Private buyers snapped up many items like the vintage cars, while the maze met the grisliest fate, chopped into wood and sold to locals for their personal projects.

Despite the council’s grand plan for the redeveloped swimming complex, QEII’s fresh design would not last long. Although the pool and stadium both survived the 2010 Christchurch earthquake, the next disaster in 2011 damaged them beyond repair. Demolition on QEII’s remnants began in August 2012, making space for two single-sex high schools to open in 2019.

However all of QEII Fun Park is not lost – miraculously, some attractions still survive to this day. The bumper boats and sack slide made their way to Tāhunanui Beach’s Nelson Fun Park. Driveworld’s Richard Smit still operates its mini jeeps at A&P shows and the annual Christchurch Easter show, and he holds onto bits and pieces of the trucks and excavators, gradually documenting his repairs on these historical items with his Driveworld Facebook page.

Though the council reopened the gym and swimming complex in 2018 as Taiora QEII Recreation and Sport Centre, trawling through Christchurch Facebook groups today reveals thousands of parkgoers nostalgic for the amusement park as the real main event. They reminisce on the burns they suffered sneaking onto the giant slide at night, the epic showdowns between parent and child on the raceway, or the mini golf and bumper boats of their childhood stomping grounds. QEII may be long gone, but the memories live on.